This is a post about multiplying polynomials, convolution sums and the

connection between them.

Multiplying polynomials

Suppose we want to multiply one polynomial by another:

This is basic middle-school math – we start by cross-multiplying:

And then collect all the terms together by adding up the coefficients:

Let’s look at a slightly different way to achieve the same result. Instead of

cross multiplying all terms and then adding up, we’ll focus on what terms appear

in the output, and for each such term – what its coefficients are going to be.

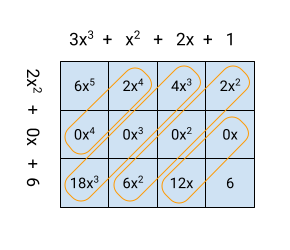

This is easy to demonstrate with a table, where we lay out one polynomial

horizontally and the other vertically. Note that we have to be explicit about

the zero coefficient of x in the second polynomial:

The diagonals that add up to each term in the output are highlighted. For example,

to get the coefficient of in the output, we have to add up:

- The coefficient of in the first polynomial, multiplied by the

constant (coefficient of ) in the second polynomial - The coefficient of in the first polynomial, multiplied by the

coefficient of in the second polynomial

in the second polynomial - The coefficient of

in the first polynomial, multiplied by the

in the first polynomial, multiplied by the

coefficients of in the second polynomial

(if the second polynomial had a term, there would be another

component to add)

For what follows, let’s move to a somewhat more abstract representation: a

polynomial P can be represented as a sum of coefficients

multiplied by corresponding powers of x :

Suppose we have two polynomials, P and R. When we multiply them together,

the resulting polynomial is S. Based on our insight from the table diagonals

above, we can say that for each k:

And then the entire polynomial S is:

It’s important to understand this formulation, since it’s key to this

post. Let’s use our example polynomials to see how it works. First, we represent

the two

polynomials as sequences of coefficients (starting with 0, so the coefficient

of the constant is first, and the coefficient of the highest power is last):

In this notation, is the first element in the list for P, etc.

To calculate the coefficient of in the product:

Expanding the sum for all the non-zero coefficients of P:

Similarly, we’ll find that , and so on, resulting

in the final polynomial as before:

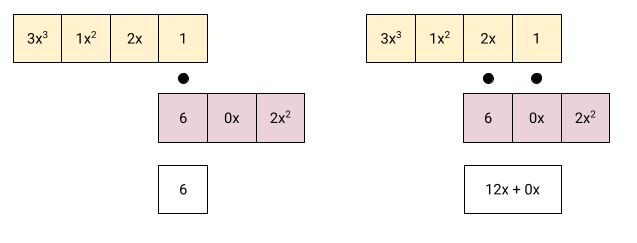

There’s a nice graphical approach to multiply polynomials using this idea of

pairing up sums for each term in the output:

We start with the diagram on the left: one of the polynomials remains in its

original form, while the other is flipped around (constant term first, highest

power term last). We line up the polynomials vertically, and multiply the

corresponding coefficients: the constant coefficient of the output is just the

constant coefficient of the first polynomial times the constant coefficient of

the second polynomial.

The diagram on the right shows the next step: the second polynomial is shifted

left by one term and lined up vertically again. The corresponding coefficients

are multiplied, and then the results are added to obtain the coefficient of x

in the output polynomial.

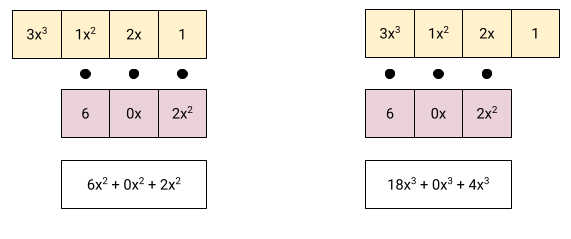

We continue the process by shifting the lower polynomial left:

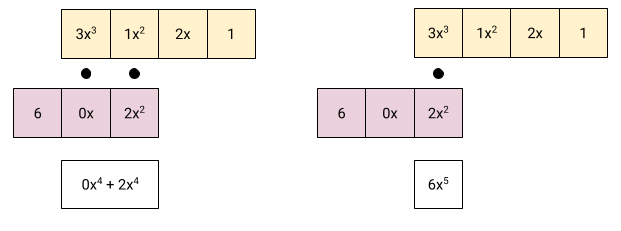

Calculating the coefficients of and then . A couple more

steps:

Now we have all the coefficients of the output. Take a moment to convince

yourself that this approach is equivalent to the summation shown just

before it, and also to the “diagonals in a table” approach shown further up.

They all calculate the same thing !

Hopefully it should be clear why the second polynomial is “flipped” to perform

this procedure. This all comes down to which input terms pair up to calculate

each output term. As seen above:

While the index i moves in one direction (from the low power terms to the

high power terms) in P, the index k-i moves in the opposite direction in

R.

If this procedure reminds you of computing a convolution between two arrays,

that’s because it’s exactly that!

Signals, systems and convolutions

The theory of signals and systems is a large topic (typically taught for one

or two semesters in undergraduate engineering degrees), but here I want to focus

on just one aspect of it which I find really elegant.

Let’s define discrete signals and systems first, restricting ourselves to 1D

(similar ideas apply in higher dimensions):

Discrete signal: An ordered sequence of numbers with integer

indices . Can also be

thought of as a function .

Discrete system: A function mapping input signals to output

signals . For example, is a system that scales

all signals by a factor of two.

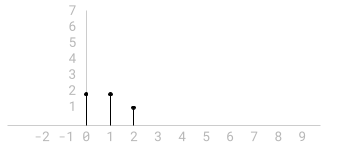

Here’s an example signal:

This is a finite signal. All values not explicitly shown in the chart are

assumed to be 0 (e.g. , , and so

on).

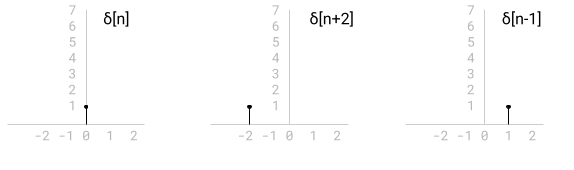

A very important signal is the discrete impulse:

In graphical form, here’s , as well as a couple of time-shifted

variants of it. Note how we shift a signal left and right on the horizontal

axis by adding to or subtracting from n, correspondingly. Take a moment to

double check why this works.

The impulse is useful because we can decompose any discrete signal into

a sequence of scaled and shifted impulses. Our example signal

has three non-zero values at indices 0, 1 and 2; we can

represent it as follows:

More generally, a signal can be written as:

(for all k where is nonzero)

In the study of signals and systems, linear and time-invariant (LTI) systems

are particularly important.

Linear: suppose is the output of a system for input signal

, and similarly is the output for .

A linear system outputs for the input

where a and b are constants.

Time-invariant: if we delay the input signal by some constant:

, the output is similarly delayed: . In other

words, the response of the system has a similar shape, no matter when the

signal was received (it behaves today similarly to the way it behaved

yesterday).

LTI systems are important because of the decomposition of a signal into impulses

discussed above. Suppose we want to characterize a system: what it does to an

arbitrary signal. For an LTI system, all we need to describe is its response to

an impulse!

If the response of our system to is , then:

- Its response to is , for any

constant c, because the system is linear. - Its response to is , for any time shift

k, because the system is time-invariant.

We’ll combine these and use linearity again (note that in the following

are just constants); the response to a signal decomposed into a sum

of shifted and scaled impulses:

Is:

This operation is called the convolution between sequences and

, and is denoted with the operator:

Let’s work through an example. Suppose we have an LTI system with the following

response to an impulse:

![Impulse response h[n]](https://newsinside2you.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/hn-impulse-response.png)

The response has , and zeros everywhere else.

Recall our sample signal from the top of this section (the sequence 2, 2, 1).

We can decompose it to a sequence of scaled and shifted impulses, and then

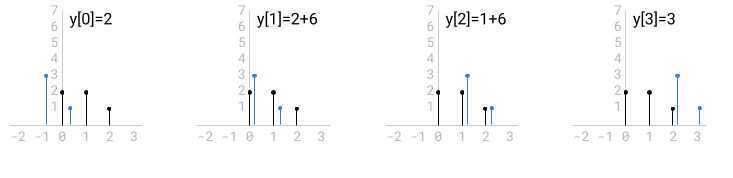

calculate the system response to each of them. Like this:

![Decomposed x[n] and the h[n] for each component](https://newsinside2you.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/hn-response-decompose.png)

The top row shows the input signal decomposed into scaled and shifted impulses;

the bottom row is the corresponding system response to each input. If we carefully

add up the responses for each n, we’ll get the system response

to our input:

![y[n] full system response](https://newsinside2you.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/yn-response.png)

Now, let’s calculate the same output, but this time using the convolution sum.

First, we’ll represent the signal x and the impulse response h as sequences

(just like we did with polynomials), with first, then

etc:

The convolution sum is:

Recall that k ranges over all the non-zero elements in x. Let’s calculate

each element of (noting that h is nonzero only for indices

0 and 1):

All subsequent values of y are zero because k only ranges up to 2 and

.

If you look carefully at this calculation, you’ll notice that h is “flipped”

in relation to x, just like with the polynomials:

- We start with (black) and flipped (blue), and line up the first

non-zero elements. This computes - In subsequent steps, is slides right, one element at a time,

and the next value of y is computed by adding up the element-wise products

of the lined up x and h.

Just like with polynomials , the reason why one of the inputs is flipped is

clear from the definition of the convolution sum, where one of the the indices

increases (k), while the other decreases (n-k).

Properties of convolution

The convolution operation has many useful algebraic properties: linearity, associativity,

commutativity, distributivity, etc.

The commutative property means that when computing convolutions graphically,

it doesn’t matter which of the signals is “flipped”, because:

And therefore:

But the most important property of the convolution is how it behaves in the

frequency domain. If we denote as the Fourier transform

of signal f, then the convolution theorem states:

The Fourier transform of a convolution is equal to simple multiplication

between the Fourier transforms of its operands. This fact – along with advanced

algorithms like FFT – make it possible to

implement convolutions

very efficiently.

This is a deep and fascinating topic, but we’ll leave it as a story for

another day.