There’s a bushy tree in my backyard with these dark red fruit — the kind that makes some primal instinct scream at you across millennia,

but you can’t tell if it wants you to eat them or not.

I used a plant app to identify it (like a true horticultural expert): it’s Prunus laurocerasus, or cherry laurel.

The most innocent of names. Apparently a popular landscaping choice given its dense foliage.

Apparently also a popular source of poison used by the ancient Roman Emperor Nero to assassinate his enemies.

My own tree, not producing fruit at the time of writing.

An unwitting victim could drink water from their local well, or from a glass at a lively dinner, never detecting cyanide distilled

from cherry laurel leaves. This was likely thanks to Locusta, Nero’s go-to poisoner, whom he freed from prison after she poisoned

his step-father (why let talent go to waste?). Historians speculate on her exact arsenal, like deadly nightshade, mushrooms,

etc. — yet cherry laurel is notable: its leaves, stem, seeds, and unripe fruit are all

toxic, and cyanide is fast-acting.

I read, aghast, that Locusta was ordered to test a poison “on children” in preparation for assassinating the heir to the throne.[1]

Locusta of Gaul – Nero’s Notorious Poison Maker.

Ancient Rome was brutal, but poisoning children? I read another source — “it was then tried on a kid” — and kept reading —

“the animal did not die until the lapse of five hours”.[2]Medical Jurisprudence. Paris & Fonblanque (1823)

A goat, she tested on a baby goat. Not that she was any short of

deplorable; she regularly tested on animals, as well as slaves.

Fast forward from 54 AD to 1819 — you’ll find the same plant that sent unfortunate ancient Romans to their convulsive deaths

is now inside custards and puddings at afternoon tea. Cherry laurel leaves provided cheap almond-like flavor. When carelessly

prepared, these custards could be dangerous, causing five kids (human this time) at an English boarding school to fall severely

ill for three days[2]Medical Jurisprudence. Paris & Fonblanque (1823)

— never thought “dangerous custard” would be two words I’d write together, as if they’d describe a villain in an Agatha Christie novel.

Incompetent cooks aside, it was still generally known that cherry laurel was risky to eat. A book from 1837, grandiosely titled

“Two Thousand Five Hundred Practical Recipes in Family Cookery”,

includes a recipe that uses a laurel leaf. It’s immediately

followed up with some Victorian-era sass: “Note. — It might be supposed that this dish was [invented for] the express purpose of giving trouble; the

laurel leaf is poisonous.” [3]Two Thousand Five Hundred Practical Recipes in Family Cookery. Jennings (1837)

Who wouldn’t rub

cyanide on their eyes to treat eye strain? [4]Cherry-Laurel Lotion. National Museum of American History

So, not to eat, then. But shaving cream? Shampoo? Facial cleanser? “Cherry laurel lotion” could do the trick, apparently having

soothing qualities. Surely, nothing says “self-care” quite like slathering diluted cyanide on your face.[5,Splash it all over: A brief history of aftershave. Withey (2016)

6]Instructions and cautions respecting the selection and use of perfumes, cosmetics and other toilet articles, with a comprehensive collection of formulae and directions for their preparation. Cooley (1873)

Today, you’re not likely to find cyanide in your custards or shaving cream. You might, however, find it in your Sunday dinner — like

the two Italians who had mistaken cherry laurel for bay leaves and ended up in the hospital, after eating a slightly almond-y guinea

fowl.[7]Piante velenose della flora italiana nell’esperienza del Centro Antiveleni di Milano. Banfi et al. (2012)

They weren’t alone; 147 Italians from 1995-2007 had similar experiences,[8]Risk of Poisoning from Garden Plants: Misidentification between Laurel and Cherry Laurel. Malaspina et al. (2022)

along with many an unfortunate grazing animal.

Centuries after Locusta’s experiments, goats still have it rough, occasionally dying from eating cherry laurel leaves.

Spice, or poison?

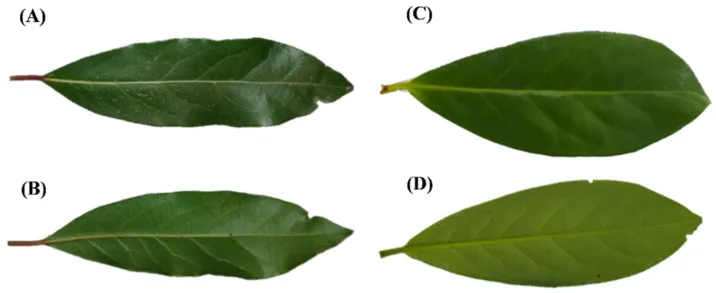

Bay leaves (A & B) look too similar to cherry laurel (C & D). [8]Risk of Poisoning from Garden Plants: Misidentification between Laurel and Cherry Laurel. Malaspina et al. (2022)

There’s also this gardener, who had a close call:

[A] correspondent told me about the time he filled his car with bagged shreddings from his large cherry laurel and set off

for the [trip]. On the way, he could smell almonds and thought ‘Hmmm, cake!’ before realising what he was smelling. He opened

all the car windows and suffered no ill effects (other than the disappointment of not having any cake).

Source: The Poison Garden [9]The Poison Garden.

So, beware suspicious bay leaves, beware Roman emperors who employ poisoners, and beware unexpected games

of “Is it cake?”.

Despite all the above (the assassinations, the hospitalizations, the dead goats), part of the cherry laurel is actually edible.

You can eat the fruit as long as it’s ripe. Travel to the Black Sea region of Turkey, and you’ll find cherry laurel fruit

(or karayemis) in many different forms — fresh, dried, roasted, pickled, salted, in jams or cakes, and more.[10,An Unsung Prunus. Potentilla (2023)

11]An Important Genetic Resource For Turkey: Cherry Laurel. Yazıcı et al. (2011)

Supposedly they taste kind of like cherries, sour and sweet, and slightly bitter/astringent/sharp — basically all of the

adjectives. If you can describe it better than the Internet, let me know. Too bitter, though, and you’d better

spit it out to avoid larger concentrations of cyanide.

Crushing a leaf from the tree in my backyard, I don’t smell much other than crushed plant — no distinctive almond scent.

Makes me wonder if I’m one of the unlucky 20-40% of humans who can’t smell cyanide,[12]Medical Management Guidelines for Hydrogen Cyanide

or if my backyard has, in fact, no connection to Ancient Rome at all. Can’t tell which of those is worse.